What is Peak Car?

February 28, 2019

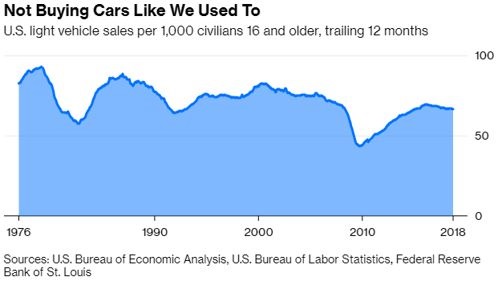

Peak car is a hypothesis that motor vehicle distance traveled per capita, predominantly by private car, has peaked and will now fall in a sustained manner. The automobile once both a badge of success and the most convenient conveyance between points A and B is falling out of favor in cities around the world. Auto sales in the U.S., after four record or near-record years, are declining and analysts say they may never again reach those heights.

A decade ago the auto industry predicted annual global vehicle sales would top 100 million by now, but they have stalled instead, falling to 94.2 million last year, down 1 million from 2017. Researcher IHS Markit predicts the 100 million vehicle milestone will be surpassed in the next decade.

Interestingly, only 26 percent of U.S. 16-year-olds obtained a driver’s license in 2017. That is almost half of what would have been obtained just 36 years ago, according to Sivak Applied Research. Likewise, the annual number of 17-year-olds taking driving tests in the U.K. has fallen 28 percent in the past decade.

Meanwhile, mobility services are multiplying rapidly, with everything from electric scooters to robo-taxis trying to establish a foothold in the market. Increasingly, major urban centers such as London, Madrid, and Mexico City are restricting cars’ access. Such constraints, plus the expansion of the sharing economy and the advent of the autonomous age, have made automakers nervous and considering the possibility that the world is approaching “peak car”.

Globally, the success of mobility services is already chipping away at long-term forecasts for the industry. IHS last year trimmed 1.4 million vehicles from its 2030 prediction after studying the new options for getting around, says Henner Lehne, vice president for forecasting.

IHS sees the biggest impact of mobility services coming in China. Auto sales there plunged 18 percent in January, an unprecedented seventh consecutive monthly decline, as commuters rapidly embraced ride-hailing. Last year, 550 million Chinese took 10 billion rides with the Didi ride-hailing service. That’s twice as many rides as Uber provided globally in 2018.

China’s car sales momentum may have slowed, but that is better than the situation in established markets such as the U.S. and Western Europe, says Jeff Schuster, senior vice president for forecasting at researcher LMC Automotive.

The tipping point worldwide will come at the end of the next decade, when self-driving cars start gaining traction, predicts Mark Wakefield, head of the automotive practice at consultant AlixPartners. Replacing a taxi driver with a robot cuts 60 percent from a ride’s cost, making travel in a driverless cab much cheaper than driving your own car.

What are not cheaper are sticker prices. To boost profit margins, automakers have been loading cars with expensive extras and high-tech touches, pushing the average price of a new car in the U.S. to a record $37,777 by the end of last year, according to Kelley Blue Book. That has caused many people to hold on to their existing rides longer; the average age of autos on U.S. roads reached a record 11.7 years in 2018, according to IHS.

Nonetheless, auto executives are predicting a prosperous future for the traditional automobile. Population growth and economic expansion should fuel ever-growing sales, even in mature markets, says Elaine Buckberg, chief economist for General Motors Co. Yet GM is placing big bets on mobility investments and cutting back on carmaking. GM is planning to close five North American car factories, starting with an Ohio plant in March, while plowing $1 billion a year into developing self-driving cars. Employment at its autonomous tech arm, GM Cruise, has grown to more than 1,000 workers, from just 30 in 2016. GM, which plans to debut a robo-taxi service late this year, already offers car-sharing through its Maven unit and has invested $500 million in Lyft’s ride-hailing business.

In Europe, Daimler AG and BMW AG on Feb. 22 said they will pour more than 1 billion into their jointly owned car-sharing and ride-hailing businesses. The year-old umbrella venture, ShareNow, is expected to become the world’s largest car-sharing operator; it will weigh purchases of startups or established players along with collaborations, Daimler said.

Indeed, automakers may talk a good game about moving metal, but increasingly they are chasing profits expected to come from services that charge by the mile. Revenue from those “disruptive” options will grow to 25 percent of the transportation market by 2030, from 1 percent now, according to McKinsey & Co. While earnings from traditional carmaking decline, profits from mobility services will come to dominate the $634 billion that the auto industry is expected to make in 2030, Accenture says. “Right now, everyone still hopes to sell more cars. I haven’t come across a single company that forecasts a decline,” says Philipp Kampshoff, a McKinsey partner who specializes in transportation. “But there is just a huge profit pool emerging, and everybody is thinking, How can I tap into it?”

Automakers are relying on their century-old manufacturing businesses to generate profits to finance their future in shared and electric driverless cars. The first big challenge is persuading new car buyers to give up gas guzzlers and go electric, a shift energy researcher Bloomberg NEF predicts will occur in the next decade, with China leading the charge. Electrified cars connected to the internet will enable cheap forms of mobility that will make owning an auto expensive and obsolete. “Before peak car, there’s going to be a peak in internal combustion engine vehicles,” says Colin McKerracher, head of advanced transport analysis for BNEF. “That will have a big effect on automakers’ strategies, because investment has a habit of chasing growth.”

Ultimately, individual car ownership will give way to having a mobility app on your phone, where an automobile is but one mode available, says Kersten Heineke, a McKinsey transportation specialist. “The main question around peak car is how much of this will trickle down to smaller cities and the countryside,” Heineke says.

The minority of the world’s population living in those wide-open spaces by midcentury will likely still own vehicles, because the distances are too large and population density too small for many mobility services to operate profitably. But urban dwellers may well have to spend a day in the country to catch a glimpse of that 20th century show pony known as a car.

Keith Naughton and David Welch. (2019). “This Is What Peak Car Looks Like”. Retrieved from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2019-02-28/this-is-what-peak-car-looks-like.